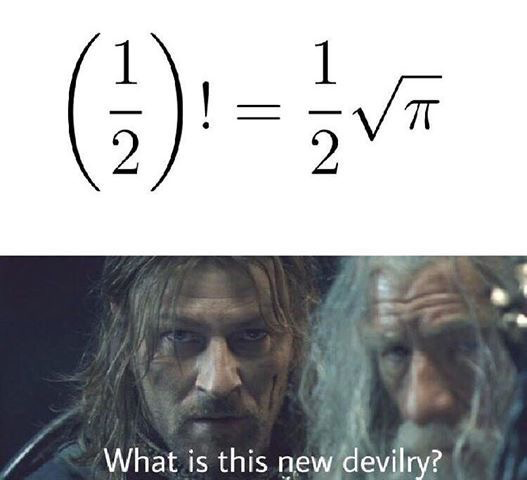

Factorial of non-integer values

Demonstrating the concept of taking the factorial of non-integer values

Seeing this meme was the first time I came across this result. In terms of proving it, there are a couple of bits which may seem difficult to understand, but I have tried to explain them as well as I can, and have provided some links at the end which may be useful.

The factorial operator can be defined as the following:

\[n!=n\cdot(n-1)\cdot(n-2)\cdot(n-3)\cdots3\cdot2\cdot1\]Or in a more compact form:

\[n!=\prod_{k=1}^nk\]However, this is only true for integer values of $n$. In order to prove the given result, the factorial operation must be defined for non-integer values. This can be done using the gamma function. The integral form of the gamma function is

\[\Gamma(z)=\int_0^\infty x^{z-1}e^{-x}dx\]In this form it is difficult to see how this could be used to find $(\frac{1}{2})!$. However, it can be equated to a general expression for finding the factorial of any real or complex $z$, with $\Re(z)>0$. This expression can be found inductively. First, we must find $\Gamma(1)$:

\[\begin{aligned} \Gamma(1)&=\int_0^{\infty}e^{-x}dx \\ &=\left[-e^{-x}\right]_0^{\infty} \\ &=\left(\lim_{x\to\infty}-e^{-x}\right)+e^{-0} \\ &=1 \end{aligned}\]Next, we find $\Gamma(z+1)$:

\[\Gamma(z+1)=\int_0^{\infty}x^ze^{-x}dx\]This can be evaluated by integrating by parts:

\[\begin{aligned} \Gamma(z+1)&=\left[-x^ze^{-x}\right]_0^\infty+z\int_0^{\infty}x^{z-1}e^{-x}dx \\ &=\left[-x^ze^{-x}\right]_0^\infty+z\Gamma(z) \\ &=\left(\lim_{x\to\ \infty}-x^ze^{-x}\right)+z\Gamma(z) \\ &=z\Gamma(z) \end{aligned}\]Combining this with $\Gamma(1)=1$ we can see that

\[\begin{aligned} \Gamma(z)&=(z-1)\Gamma(z-1) \\ &=(z-1)(z-2)\Gamma(z-2) \\ &=(z-1)(z-2)\cdots(z-(z-2))(z-(z-1))\Gamma(z-(z-1)) \\ &=(z-1)(z-2)\cdots2\cdot1 \end{aligned}\]And so, we get that

\[\Gamma(z)=(z-1)!\]For $(\frac{1}{2})!$ let $z=\frac{3}{2}$:

\[\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)=\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)!\]$\Gamma(\frac{3}{2})$ can be given in terms of $\Gamma(\frac{1}{2})$ by the property $\Gamma(z+1)=z\Gamma(z)$:

\[\begin{aligned} \Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)&=\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\Gamma\left(\frac{1}{2}\right) \\ &=\frac{1}{2}\int_0^{\infty}x^{-\frac{1}{2}}e^{-x}dx \end{aligned}\]If we substitute $x=u^2$, with $dx=2udu$, we get

\[\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)=\int_0^{\infty}e^{-u^2}du\]The right hand side is known as the Gaussian integral. To evaluate this integral we must first square both sides. This may seem strange, however, in order to solve it the integral must be transformed from cartesian to polar coordinates.

\[\begin{aligned} \left(\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)\right)^2&=\left(\int_0^{\infty}e^{-u^2}du\right)^2 \\ &=\left(\int_0^{\infty}e^{-u^2}du\right)\left(\int_0^{\infty}e^{-v^2}dv\right) \\ &=\int_0^{\infty}\int_0^{\infty}e^{-(u^2+v^2)}dudv \end{aligned}\]The transformation to polar coordinates comes from making the substitution $u=r\cos\theta$ and $v=r\sin\theta$. And so, in terms of the new variables, $(r, \theta)$, the integral is taken over $0\leqslant r\leqslant\infty$ and $0\leqslant\theta\leqslant\frac{\pi}{2}$, and $dudv$ becomes $rdrd\theta$. This linear transformation can be represented by the Jacobian matrix:

\[\begin{aligned} \textbf{J}_{\textbf{F}}(r,\theta)= \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial u}{\partial r}&\frac{\partial u}{\partial\theta}\\ \frac{\partial v}{\partial r}&\frac{\partial v}{\partial\theta}\\ \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\theta&-r\sin\theta\\ \sin\theta&r\cos\theta\\ \end{bmatrix} \\ \end{aligned}\]Taking the determinant of $\textbf{J}_{\textbf{F}}$ gives

\[|\textbf{J}_{\textbf{F}}(r,\theta)|=r\cos^2\theta-(-r\sin^2\theta)=r\]And so, the integral becomes

\[\left(\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)\right)^2=\int_0^{\infty}\int_0^{\frac{\pi}{2}}e^{-r^2}rdrd\theta\]The way we’ve transformed the coordinates may seem a bit confusing and abstract. I have put some links at the bottom of the page which better explain how this transformation is made and what’s actually going on when the Jacobian matrix is used.

Splitting the double integral makes it easier to see how it can be evaluated:

\[\begin{aligned} \left(\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)\right)^2&=\left(\int_0^{\frac{\pi}{2}}d\theta\right)\left(\int_0^{\infty}e^{-r^2}rdr\right) \\ &=\left(\left[\theta\right]_0^{\frac{\pi}{2}}\right)\left(\int_0^{\infty}e^{-r^2}rdr\right) \\ &=\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)\left(\int_0^{\infty}e^{-r^2}rdr\right) \\ \end{aligned}\]To evaluate the second integral, we make the substitution $t=-r^2$, with $dt=-2rdr$:

\[\begin{aligned} \left(\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)\right)^2&=\frac{\pi}{2}\left(-\int_0^{-\infty}e^tr\frac{dt}{2r}\right) \\ &=-\frac{\pi}{4}\left(\int_0^{-\infty}e^tdt\right) \\ &=-\frac{\pi}{4}\left[\left(\lim_{t\to-\infty}e^t\right)-e^0\right] \\ &=-\frac{\pi}{4}(0-1) \\ &=\frac{\pi}{4} \end{aligned}\]Taking the square root of both sides gives

\[\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}\]We showed earlier that $\Gamma(\frac{3}{2})=(\frac{1}{2})!$. And so, using this we get the desired result:

\[\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)!=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}\]I think the reason that this result is so mind-blowing is that we have a preconceived understanding of what $n!$ means, though, it is only valid for positive integers. And after struggling with the idea of applying that meaning to a fraction it turns out that it is actually equal to a factor of $\pi$! Amazing.

We showed earlier that $\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)=\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\Gamma\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)$. And so, from the result we just proved, it follows that

\[\Gamma\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)=\sqrt{\pi}\]If we recall the property $\Gamma(z)=(z-1)!$, then we see that

\[\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)!=\sqrt{\pi}\]Crazy.

Useful links: