Given some medium, e.g. water,

containing some material, say salt, the material will DIFFUSE from the

concentrated area to the dilute area. Diffusion can be generalised by Fick’s law:

J = − D d C d x J = -D \frac{\text{d} C}{\text{d} x} J = − D d x d C

where J J J D D D δ t \delta t δ t

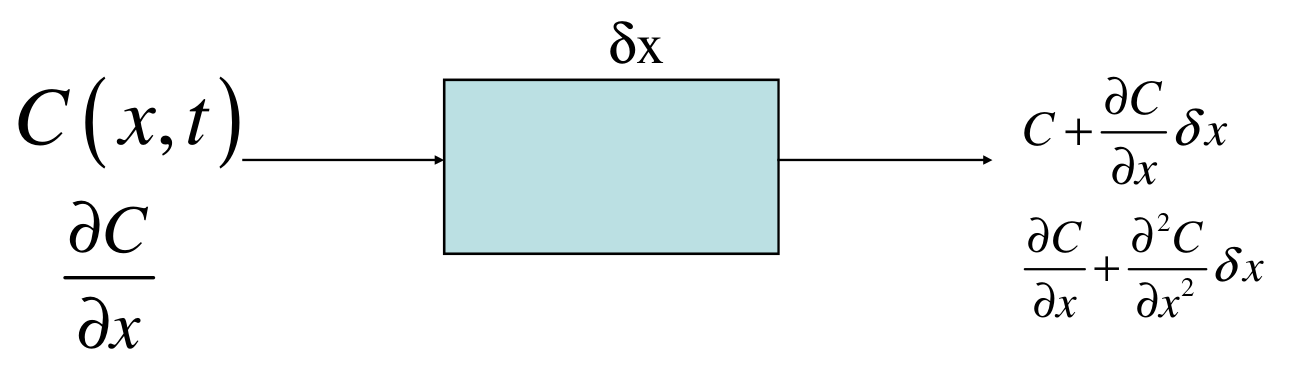

MOLES IN − MOLES OUT = Accumulated MOLES \text{MOLES IN} - \text{MOLES OUT} = \text{Accumulated MOLES} MOLES IN − MOLES OUT = Accumulated MOLES − D ∂ C ∂ x A δ t − [ − D ( ∂ C ∂ x + ∂ 2 C ∂ x 2 δ x ) ] A δ t = V Δ C . -D\frac{\partial C}{\partial x} A \delta t - \left[ -D \left( \frac{\partial

C}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2}\delta x \right) \right]

A\delta t = V\Delta C. − D ∂ x ∂ C A δ t − [ − D ( ∂ x ∂ C + ∂ x 2 ∂ 2 C δ x ) ] A δ t = V Δ C . Replacing V = A δ x V = A\delta x V = A δ x

− D ∂ C ∂ x A δ t − [ − D ( ∂ C ∂ x + ∂ 2 C ∂ x 2 δ x ) ] A δ t = A δ x Δ C . -D\frac{\partial C}{\partial x} A \delta t - \left[ -D \left( \frac{\partial

C}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2}\delta x \right) \right]

A\delta t = A\delta x \Delta C. − D ∂ x ∂ C A δ t − [ − D ( ∂ x ∂ C + ∂ x 2 ∂ 2 C δ x ) ] A δ t = A δ x Δ C . − D ∂ C ∂ x A δ t + D ( ∂ C ∂ x + ∂ 2 C ∂ x 2 δ x ) A δ t = A δ x Δ C . -D\frac{\partial C}{\partial x} A \delta t + D\left( \frac{\partial

C}{\partial x} + \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2}\delta x \right)

A\delta t = A\delta x \Delta C. − D ∂ x ∂ C A δ t + D ( ∂ x ∂ C + ∂ x 2 ∂ 2 C δ x ) A δ t = A δ x Δ C . − D ∂ C ∂ x + D ∂ C ∂ x + D ∂ 2 C ∂ x 2 δ x = δ x Δ C δ t . -D\frac{\partial C}{\partial x} + D\frac{\partial

C}{\partial x} + D\frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2}\delta x

= \delta x \frac{\Delta C}{\delta t}. − D ∂ x ∂ C + D ∂ x ∂ C + D ∂ x 2 ∂ 2 C δ x = δ x δ t Δ C . D ∂ 2 C ∂ x 2 = Δ C δ t . D\frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2}= \frac{\Delta C}{\delta

t}. D ∂ x 2 ∂ 2 C = δ t Δ C . Taking the limit as the right hand side goes the zero we see that the above

equation approaches

∂ C ∂ t = D ∂ 2 C ∂ x 2 \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2} ∂ t ∂ C = D ∂ x 2 ∂ 2 C This is the 1D diffusion equation over a small control volume V V V

Let us consider the case of transient diffusion through a semi-infinite

geometry. The boundary conditions in this case are

at t < 0 t < 0 t < 0 C A = C A , i , C_{A} = C_{A,i}, C A = C A , i ,

at t > 0 t > 0 t > 0 C A → C A , i C_{A} \to C_{A,i} C A → C A , i x = 0 x = 0 x = 0

at t > 0 t > 0 t > 0 C A = C A , s C_{A} = C_{A,s} C A = C A , s

Let us define a similarity variable, η \eta η x x x t t t

η = x 4 D t \eta = \frac{x}{\sqrt{4Dt}} η = 4 D t x We can now re-write the diffusion equation in terms of the similarity variable.

∂ C ∂ x = ∂ C ∂ η ∂ η ∂ x \frac{\partial C}{\partial x} = \frac{\partial C}{\partial \eta}\frac{\partial \eta}{\partial x} ∂ x ∂ C = ∂ η ∂ C ∂ x ∂ η ∂ η ∂ x = 1 4 D t \frac{\partial \eta}{\partial x} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4Dt}} ∂ x ∂ η = 4 D t 1 And so, in terms of η \eta η

∂ C ∂ x = 1 4 D t ∂ C ∂ η \frac{\partial C}{\partial x} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4Dt}}\frac{\partial C}{\partial \eta} ∂ x ∂ C = 4 D t 1 ∂ η ∂ C The second derivative term can be broken up as

∂ 2 C ∂ x 2 = ∂ ∂ x ( ∂ C ∂ x ) = ∂ ∂ x ( d C d η ⋅ d η d x ) = ∂ 2 C ∂ η 2 d η d x ⋅ d η d x = 1 4 D t ∂ 2 C ∂ η 2 \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2} &= \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(\frac{\partial C}{\partial x}\right) \\

&= \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(\frac{\text{d} C}{\text{d} \eta}\cdot\frac{\text{d} \eta}{\text{d} x}\right) \\

&= \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial \eta^2} \frac{\text{d}\eta}{\text{d} x}\cdot\frac{\text{d}\eta}{\text{d} x} \\

&= \frac{1}{4Dt} \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial \eta^2}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} ∂ x 2 ∂ 2 C = ∂ x ∂ ( ∂ x ∂ C ) = ∂ x ∂ ( d η d C ⋅ d x d η ) = ∂ η 2 ∂ 2 C d x d η ⋅ d x d η = 4 D t 1 ∂ η 2 ∂ 2 C Taking the derivative of η \eta η

∂ η ∂ t = x 4 D ⋅ − t − 3 2 2 = − x 2 t 4 D t \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\partial \eta}{\partial t} &= \frac{x}{4D}\cdot\frac{-t^{-\frac{3}{2}}}{2} \\

&= -\frac{x}{2t\sqrt{4Dt}}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} ∂ t ∂ η = 4 D x ⋅ 2 − t − 2 3 = − 2 t 4 D t x and so,

∂ C ∂ t = d C d η d η d t = d C d η ( − x 2 t 4 D t ) \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\partial C}{\partial t} &= \frac{\text{d} C}{\text{d} \eta}

\frac{\text{d} \eta}{\text{d} t} \\

&= \frac{\text{d} C}{\text{d} \eta}\left(-\frac{x}{2t\sqrt{4Dt}}\right)

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} ∂ t ∂ C = d η d C d t d η = d η d C ( − 2 t 4 D t x ) The diffusion equation thus becomes

1 4 D t ∂ 2 C ∂ η 2 = 1 D d C d η ( − x 2 t 4 D t ) d 2 C d η 2 = − 2 x 4 D t d C d η \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{1}{4Dt}\frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial \eta^2} &= \frac{1}{D}\frac{\text{d}C}{\text{d}\eta}\left(-\frac{x}{2t\sqrt{4Dt}}\right) \\

\frac{\text{d}^2 C}{\text{d} \eta^2} &=

-\frac{2x}{\sqrt{4Dt}}\frac{\text{d}C}{\text{d}\eta}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} 4 D t 1 ∂ η 2 ∂ 2 C d η 2 d 2 C = D 1 d η d C ( − 2 t 4 D t x ) = − 4 D t 2 x d η d C Since x = η 4 D t x = \eta\sqrt{4Dt} x = η 4 D t

d 2 C d η = − 2 η d C d η \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\text{d}^2 C}{\text{d} \eta} = -2\eta \frac{\text{d} C}{\text{d} \eta}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} d η d 2 C = − 2 η d η d C Rewriting the boundary conditions in terms of η \eta η

C A = C A , i C_{A} = C_{A, i} C A = C A , i t = 0 ∴ η → ∞ t = 0 \ \therefore \ \eta \to \infty t = 0 ∴ η → ∞ C A = C A , s C_{A} = C_{A, s} C A = C A , s t > 0 ∴ η = 0 t > 0 \ \therefore \ \eta = 0 t > 0 ∴ η = 0 C A = C A , i C_{A} = C_{A, i} C A = C A , i t > 0 t > 0 t > 0 x → ∞ ∴ η = 0 x \to \infty \ \therefore \ \eta = 0 x → ∞ ∴ η = 0

The similarity variable combines the variables x x x t t t η \eta η C C C U = d C d η U = \frac{\text{d}C}{\text{d}\eta} U = d η d C

d U d η = − 2 η U \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\text{d} U}{\text{d} \eta} = - 2\eta U

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} d η d U = − 2 η U and now integrating both sides,

ln U = − η 2 + C 0 U = C 1 e − η 2 \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\ln U &= -\eta^2 + C_0 \\

U &= C_1e^{-\eta^2}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} ln U U = − η 2 + C 0 = C 1 e − η 2 Substituting back in for U U U C C C

d C d η = C 1 e − η 2 C = C 1 ∫ e − η 2 d η + C 2 \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\text{d} C}{\text{d} \eta} &= C_1e^{-\eta^2} \\

C &= C_1\int e^{-\eta^2} \text{d}\eta + C_2

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} d η d C C = C 1 e − η 2 = C 1 ∫ e − η 2 d η + C 2 Applying the boundary conditions:

C ( η = 0 ) = C s ⇒ C 2 = C s C(\eta = 0) = C_s \Rightarrow C_2 = C_s C ( η = 0 ) = C s ⇒ C 2 = C s C ( η → ∞ ) = C i ⇒ C i = C 1 ∫ 0 ∞ e − η 2 d η + C s C(\eta \to \infty) = C_i \Rightarrow C_i = C_1\int_0^\infty e^{-\eta^2}

\text{d} \eta + C_s C ( η → ∞ ) = C i ⇒ C i = C 1 ∫ 0 ∞ e − η 2 d η + C s

The above integral is half the Gaussian integral which can be evaluated to

π 2 \frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} 2 π C 1 C_1 C 1

C i = π 2 C 1 + C s C 1 = 2 π ( C i − C s ) \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

C_i = \frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}C_1 + C_s \\

C_1 = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}(C_i - C_s)

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} C i = 2 π C 1 + C s C 1 = π 2 ( C i − C s ) And so, we get the expression for C C C

C = 2 π ( C i − C s ) ∫ 0 η e − η 2 d η + C s C − C s C i − C s = 2 π ∫ 0 η e − η 2 d η \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

C = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}(C_i - C_s)&\int_0^\eta e^{-\eta^2} \text{d} \eta + C_s

\\

\frac{C - C_s}{C_i - C_s} = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}&\int_0^\eta

e^{-\eta^2}\text{d}\eta

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} C = π 2 ( C i − C s ) C i − C s C − C s = π 2 ∫ 0 η e − η 2 d η + C s ∫ 0 η e − η 2 d η The integral ∫ 0 η e − η 2 d η \int_0^\eta e^{-\eta^2} \text{d} \eta ∫ 0 η e − η 2 d η η → ∞ \eta \to \infty η → ∞ error function can be defined as

erf ( η ) ≡ 2 π ∫ 0 η e − η 2 d η \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\text{erf}(\eta) \equiv \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_0^\eta e^{-\eta^2} \text{d}

\eta

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} erf ( η ) ≡ π 2 ∫ 0 η e − η 2 d η with erf ( 1 ) = 1 \text{erf}(1) = 1 erf ( 1 ) = 1 erf ( 0 ) = 0 \text{erf}(0) = 0 erf ( 0 ) = 0

C − C s C i − C s = erf ( η ) \begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\frac{C - C_s}{C_i - C_s} = \text{erf}(\eta)

}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} C i − C s C − C s = erf ( η )